INE oil future to launch ‘as soon as possible’ – CSRC

The country's first oil future is still on the cards, but its viability as a new benchmark is far from certain

Need to know

- INE oil futures contract would be the first oil future denominated in renminbi, but complications around pricing and sanctions cause delays

- The State Council Information Office (SCIO) hopes to internationalise futures market by stabilising instruments

- The appetite for a new oil benchmark is uncertain, but regulators “besotted” with futures are keen to press ahead with the contract

The rumoured death of a Chinese oil futures contract has been greatly exaggerated. According to regulators and sources within the International Energy Exchange (INE), it will still launch its oil futures contract, which was first proposed in 2012. However there is no clear timeline.

Fang Xinghai, vice-chairman at the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC), notes that the regulator would be working this year “to further promote the preparation of crude oil futures, to launch as soon as possible,” according to a transcript of the State Council Information Office (SCIO) press conference, held on February 26 to promote the stable development of capital market reform.

The INE oil futures contract would be the first oil future denominated in renminbi (RMB). It has been seen as a gateway between China’s internal market and external traders. But industry sources say there are several complications that continue to hinder its launch, while its viability as a contract once in play is also open to question.

“This was going to be the way China opened up its futures markets to the western world, because this was going to be the first contract to be internationally accessible,” says one Hong Kong-based futures trader.

Yet without any formal announcement, he notes it appeared to have “quietly gone away” in January 2017. “This has been something they have been talking about for a long, long time. Now it seems, if anything, they are going in the other direction.”

A story from Reuters dated January 20 reported the contract had been shelved. However, on February 15, an INE executive, who asked not to be named, told Risk.net: “We definitely need to clarify everything is still ongoing, but still we cannot confirm on the launch date yet.”

Calming concerns

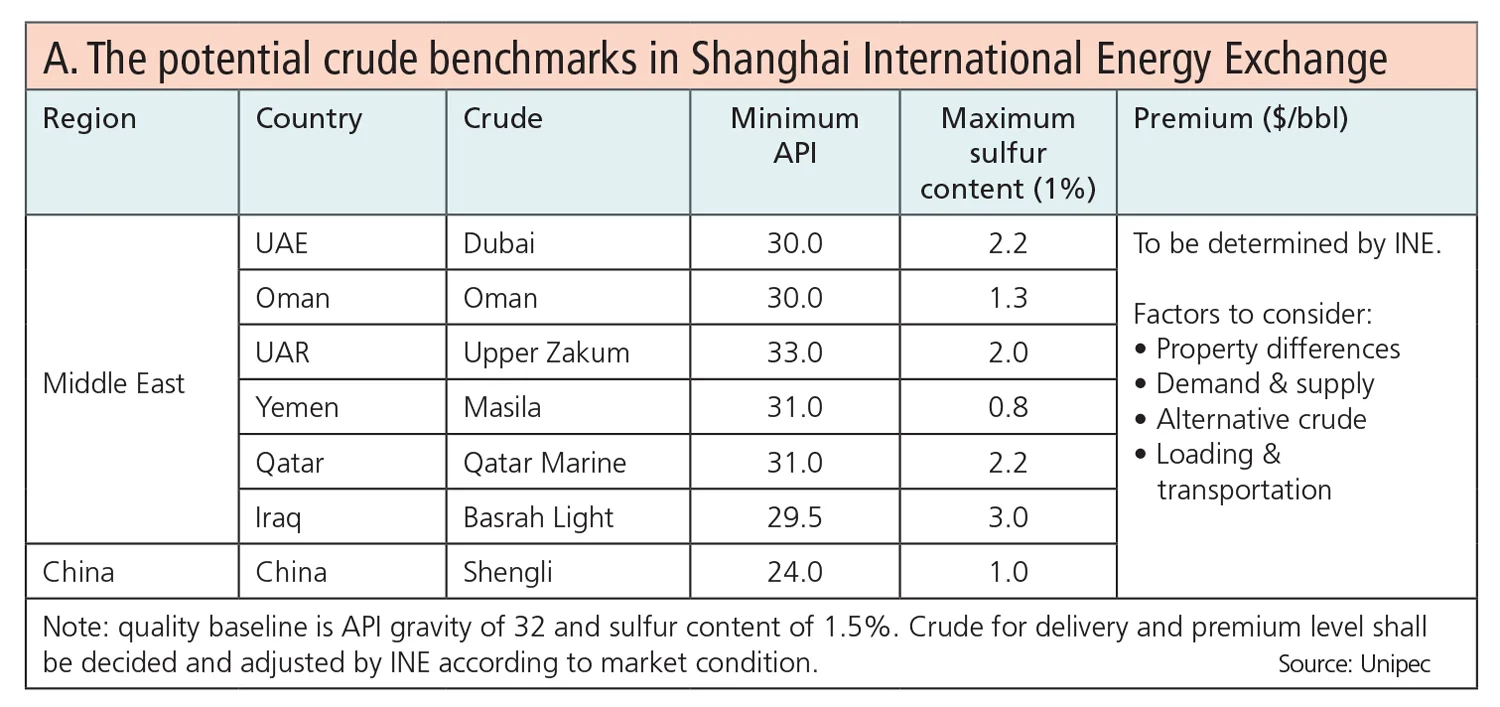

For China, a domestic oil futures market could allow it to develop its own benchmark for oil pricing, while increasing the trade of renminbi-denominated oil. The proposed contract is for 100 barrels of medium and sour crude oil, of 32 degrees American Petroleum Institute (API) gravity and 1.5% sulphur content by weight.

The deliverable grades of oil are not specified but, in a March 2016 presentation, the Chinese state oil company Sinopec’s trading arm, Unipec, published a range of expected mix of crudes from Asia and the Middle East (see table A).

Clarity of this make-up was an issue that the Futures and Options Association (FIA) raised during a public consultation in 2015, for trading firms that had to be wary of violating sanctions by purchasing from banned countries.

An insider at another Shanghai-based exchange said a further delay in the contracts launch was in part needed to give more time to sort out some uncertainty and internal issues around pricing.

“In China the energy industry is not that market-driven,” he said. “So there are a lot of vested interests. The industry giants especially are used to their, usual way of living. They have questions with the more liberalised view of market-driven pricing and so on. Some issues have to be addressed. Also in the past year there is a lot of volatility in the commodity market, so that may force the regulators to consider more carefully, or wait for better timing.”

That concern around speculation peaked in April 2016 around rebar contracts, an issue that Fang addressed at a recent SCIO press conference: “For industrial customers the futures market can play two real functions: one is price discovery, the second is to help industrial customers to guard against risks. The two most important tasks do not need such a high volume of transactions.”

By encouraging industrial users of the futures market, he noted that pricing of instruments could be made more stable. However, he also noted that the agency would still be promoting the internationalisation of the futures market.

“The artificial isolation of foreign industry customers from participating in the domestic futures market is not conducive to the formation of good [domestic futures market] pricing,” he said.

For trading purposes, the oil futures contract is proposed to have a minimum variation of 0.1 RMB per barrel, and maximum fluctuation of +/– 4% of the settlement price of the previous day would be permitted. The CSRC addressed concerns about price volatility in the futures market last year via increases in transaction costs, increases in margin requirements and the inspection of firms whose behaviour appeared to be of concern to authorities.

“From last year they have learned some lessons,” said the exchange official. “Some measures were put into place like increasing margins, increasing the cost. However I don’t know how well [the regulators] feel they are capable of controlling volatility. The reasons behind volatility are sometimes beyond what they can control. Commodity is the only vibrant derivatives market in China now, with the index futures being restricted, so there is a lot of liquidity in the market, a lot of cash in the market, and that’s hard to control. Even some of the financial industry veterans were quite concerned.”

Room for one more

The appetite among traders for a new oil benchmark is hard to gauge. No brokers or oil traders were willing to be interviewed on the subject, and several said they had not had any discussions with clients about the INE contract. Nevertheless, it is clear that of the two incumbent contracts that are used by the market as a benchmark – the Ice Brent Crude futures contract and the CME’s Nymex WTI Crude Oil futures – are both under scrutiny by the market.

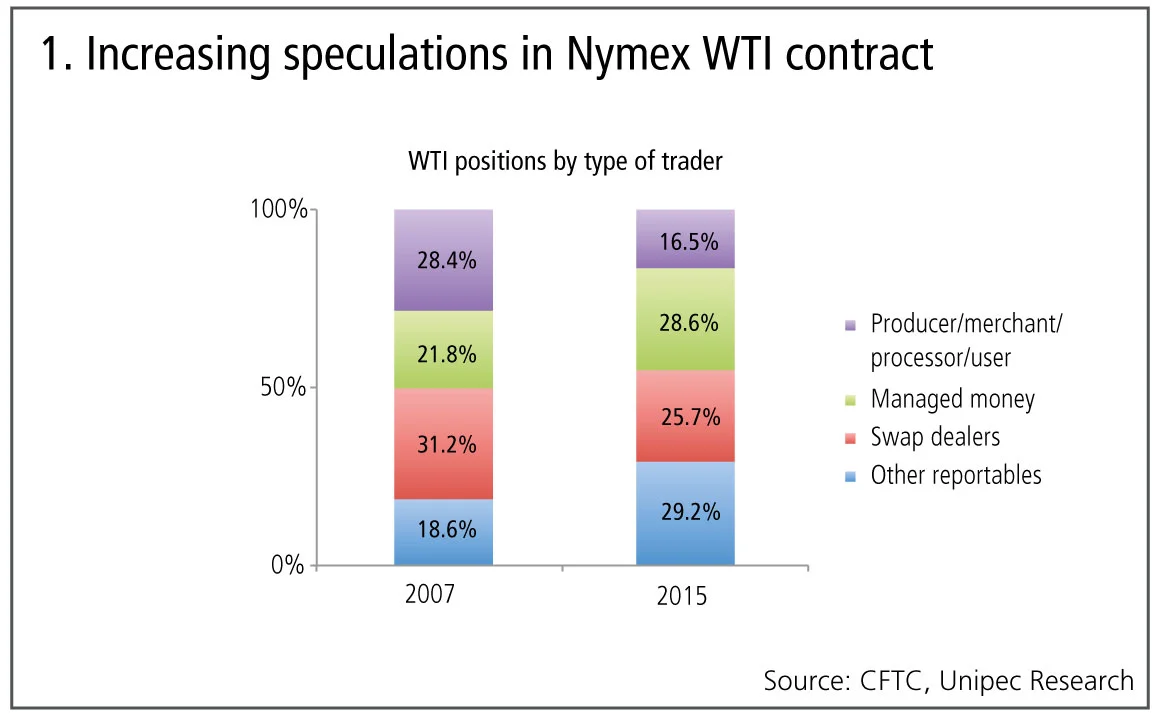

At the Fifth IEA-IEF-Opec Workshop in March 2016, Chen Bo, president of Unipec, gave a presentation that cited ‘WTI is challenged as global oil benchmark’ and ‘The dramatic changes in global oil trade, together with increasing speculations and limited liquidities of major crude benchmarks, require improvement in global crude pricing mechanism’. He drew attention both to speculation in the Nymex WTI contract (see figure 1) and to the slide in crude production in the North Sea.

The head of fundamental commodities research at one major global broker says: “Clearly, Brent production in the North Sea underlying the Brent [spot] contract has fallen a lot and people have questioned the usefulness of Brent.”

To shore the benchmark up, in 2016 price-reporting agency Platts, which publishes the existing free on board (FOB) North Sea Dated Brent assessment, announced the publication of a new assessment from March 14, 2016 “representing the value of light sweet North Sea crude oil on a cost, insurance and freight (CIF) Rotterdam basis, to be published alongside the current FOB North Sea Dated Brent assessment”.

The Dated Brent CIF Rotterdam assessment is based on the values of physical cargoes of Brent, Forties, Oseberg and Ekofisk. The existing Dated Brent price assessment reflects the spot market value of the most competitive grade at 4.30pm GMT/BST. By measuring prices into the port of Rotterdam, delivery from other geographies to the trading hub could potentially be included in the benchmark in future, which would be one way to tackle the issue of falling production.

Platts will further support the Dated Brent assessment by including Norway’s Troll crude grade in the Brent basket from January 2018.

Whether the level of concern around existing benchmarks would be enough to justify traders looking at alternative additional benchmarks would depend on case-by-case assessment of their merits. Shifting an incumbent is hard and the INE is not the only game in town.

Setting the benchmark

Other exchanges have expressed a desire to develop domestic benchmarks for oil. On November 29, 2016, Russia saw the launch of Urals Futures from the Saint Petersburg International Mercantile Exchange (Spimex), a dollar-denominated contract for 1,000 barrels with a minimum price increment set at $0.01 per barrel for trading purposes.

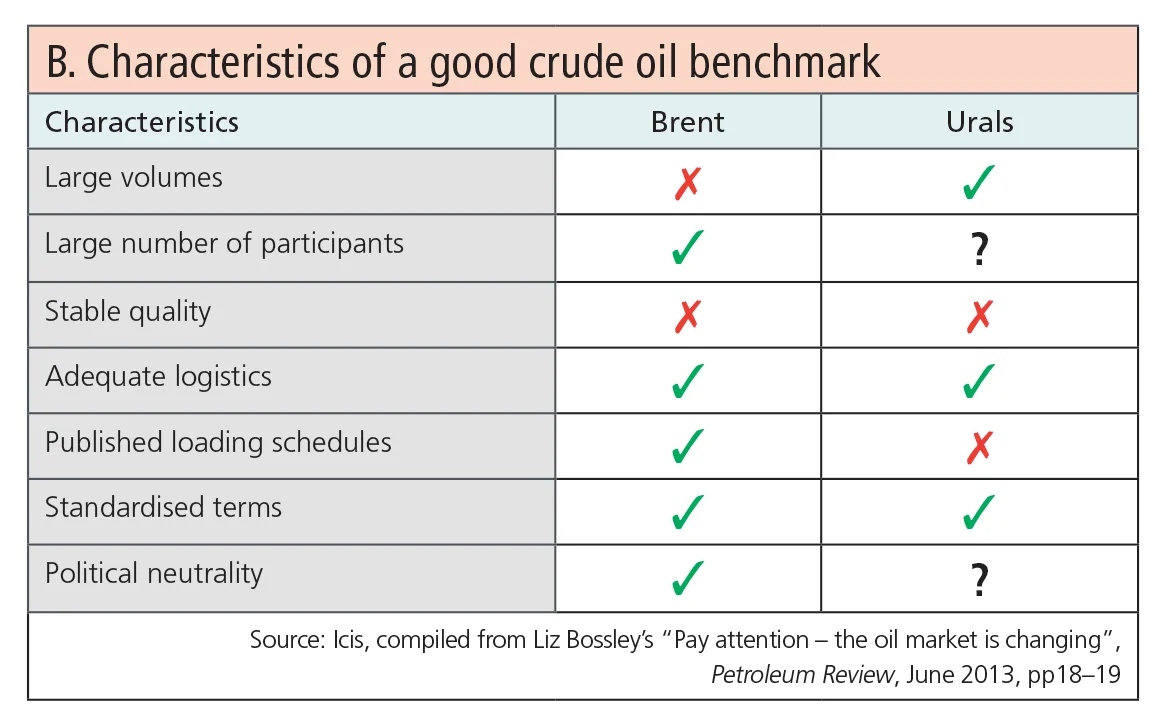

According to Spimex, the crude must meet the standard of Grade 2, Class 2, Group 1 oil by the Russian National Standards; the crude is typically of 30.68 degrees of API gravity and 1.48% sulphur level, according to a white paper on the contract published by Julien Mathonière, analyst at petrochemical market information provider Icis.

Despite the many positive characteristics of this contract (see table B), there are some serious challenges that it will face if it wants to fight for its place among the dominant futures. These provide an interesting parallel to those of the INE. Quality, critical mass of activity and the operational mechanics of trading will all be key if traders are to be encouraged away from existing benchmarks.

Firstly, at a practical level, there is the foreign exchange leg of trading. Where overseas investors in the RMB-denominated INE contract should be able to use dollars for margining, the dollar-denominated Spimex contract will require traders to use roubles to fulfil margin requirements, with variation payable in dollars but returned in roubles.

The delivery underpinning a China benchmark based only on national output would be weaker than that of a Russian benchmark; China’s 11-month daily average production was 3,971,000 barrels a day, according to the US Energy Information Administration, where Russia was producing an average of 10,526,000 a day.

The official make-up of crudes underpinning the Chinese contract is not confirmed and that creates uncertainty as to its value as a benchmark. By contrast, the volume of Urals blend going through the ports of Primorsk, Ust-Luga, and Novorossiysk exceeds 2,000,000 barrels a day, and was reaching 1,100,000 barrels a day via the Druzhba pipeline in September 2016.

In the pipeline

There are other factors that will have to be assessed before traders in western markets become enamoured with the potential for a Chinese oil future. Firstly, there is a communication problem between those traders and competent authorities in Asia-Pacific, which may explain the belief that the INE contract had died in the first place.

“We regularly spend time going to exchanges in China and India and seeing exchanges and seeing regulators and talking about what needs to be done to have their markets more accessible,” explains one financial futures trader based in Asia. “I have to say, as a general observation, we just don’t seem to get much of a response; my sense is that the exchanges are more wary of getting offside with the regulators than they are attracted by building on-exchange volumes.”

The pace of change within the regulators and exchanges can be at odds with the expectations of the market, due to administrative and internal developments, notes one Shanghai-based exchange executive.

“There are people coming in and out from the energy team, so that maybe a factor as well,” he says. “Those regulations all have to be in English, it all has to be consulted with investors – that would take time as well.”

Political issues are the elephant in the room and the new US administration’s view of trading with China is not well defined. Trading a contract in a currency that is subject to strict controls by a local government is also a potential challenge.

The direction of travel among authorities is to encourage the use of exchange-traded derivatives where possible, so that systemic risk is minimised. Consequently, it seems likely that the INE contract will be launched in line with the INE’s plans. As Mathonière notes in his white paper, regulators are “besotted” with futures markets for the transparency they bring.

“They are to commodity trades what credit cards are to retail sales. A large volume of trades can take place on regulated electronic platforms that can be monitored and measured. Over-the-counter derivatives, on the contrary, which trade an ever larger volume of transactions (swaps, options) are – like Schrödinger’s proverbial cat – withdrawn from observation and not made public.”

That description mirrors the development of the INE contract. Should the technical challenges in development be overcome, the confidence needed to build up critical mass is likely to be more encouraged by transparency than through closed-door discussions.

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@risk.net or view our subscription options here: http://subscriptions.risk.net/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@risk.net to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. Printing this content is for the sole use of the Authorised User (named subscriber), as outlined in our terms and conditions - https://www.infopro-insight.com/terms-conditions/insight-subscriptions/

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. Copying this content is for the sole use of the Authorised User (named subscriber), as outlined in our terms and conditions - https://www.infopro-insight.com/terms-conditions/insight-subscriptions/

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@risk.net

More on Energy

Energy Risk Commodity Rankings 2024: markets buffeted by geopolitics and economic woes

Winners of the 2024 Commodity Rankings steeled clients to navigate competing forces

Chartis Energy50

The latest iteration of Chartis’ Energy50 ranking

Energy trade surveillance solutions 2023: market and vendor landscape

The market for energy trading surveillance solutions, though small, is expanding as specialist vendors emerge, catering to diverse geographies and market specifics. These vendors, which originate from various sectors, contribute further to the market’s…

Achieving net zero with carbon offsets: best practices and what to avoid

A survey by Risk.net and ION Commodities found that firms are wary of using carbon offsets in their net-zero strategies. While this is understandable, given the reputational risk of many offset projects, it is likely to be extremely difficult and more…

Chartis Energy50 2023

The latest iteration of Chartis' Energy50 2023 ranking and report considers the key issues in today’s energy space, and assesses the vendors operating within it

ION Commodities: spotlight on risk management trends

Energy Risk Software Rankings and awards winner’s interview: ION Commodities

Lacima’s models stand the test of major risk events

Lacima’s consistent approach between trading and risk has allowed it to dominate the enterprise risk software analytics and metrics categories for nearly a decade

2021 brings big changes to the carbon market landscape

ZE PowerGroup Inc. explores how newly launched emissions trading systems, recently established task forces, upcoming initiatives and the new US President, Joe Biden, and his administration can further the drive towards tackling the climate crisis

Most read

- Top 10 operational risks for 2024

- Top 10 op risks: third parties stoke cyber risk

- Japanese megabanks shun internal models as FRTB bites